Christ the Plumb line: Jesus as Cornerstone, Strength, and Moral Measure of God's people

A Reflection for Holy Saturday

O God, Creator of heaven and earth: Grant that, as the crucified body of your dear Son was laid in the tomb and rested on this holy Sabbath, so we may await with him the coming of the third day, and rise with him to newness of life; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.Propers for Holy Saturday

Job 14:1-14 or Lamentations | Psalm 31:1-4, 15-16 | 1 Peter 4:1-8 | Matthew 27:57-66, or John 19:38-42

One of the gifts of my current position is being able to worship regularly with my family at Christ Church Cathedral. From our usual spot in the nave, I often find my gaze drawn to a stained glass window depicting the prophet Amos—a figure whose message has become increasingly resonant for me in recent years, especially as I’ve reflected on the nature of preaching in a divided society—partly out of the same ruminations that gave rise to The Gospel Plow.

Ever since the first Trump administration, I have been pondering with increasing urgency how one can faithfully preach in a divided country in which people's basic presuppositions about reality and facts are sometimes diametrically opposed, to say nothing of their prudential judgements about how to respond to realities they do agree on. In such a context, is preaching that takes seriously the fact that all of our actions and behavior, individually and collectively, stand under the Judgement of Christ, and that a central role of the preacher is to call attention to those areas where practices run afoul of the gospel, possible without having it dismissed as partisan?

What I’ve recognized, reflecting on that window, is this: Jesus Christ is the plumb line in the midst of a crumbling world—and this impacts how we ought to live, preach, and hope.

In the context of the Book of Amos, the vision of the plumb line occurs after various oracles against the nations. Israel and Judah are named, along with their neighbors, such as Damascus, Gaza, Tyre, Edom, Ammon, and Moab (1:3-2:16). Amos then emphasizes the call to the people to hear and heed God’s words. This call and command, as well as the warnings, are grounded in Israel’s covenant with God and their identity as his beloved people. “You only have I known, of all the families of the earth;” God says, “therefore I will punish you for all your iniquities” (Amos 3:2, NRSV). By the time we reach chapter 7, Amos has been hard at work condemning the people’s sins and failures, including, famously, their lack of care or concern for the poor. By the time we reach chapter seven, Amos has shared warnings with the people and he begins to recount five visions, of which the image of the plumb line is one:

This is what he showed me: the Lord was standing beside a wall built with a plumb line, with a plumb line in his hand. And the Lord said to me, “Amos, what do you see?” And I said, “A plumb line.” Then the Lord said,

“See, I am setting a plumb line

in the midst of my people Israel;

I will never again pass them by;

the high places of Isaac shall be made desolate,

and the sanctuaries of Israel shall be laid waste,

and I will rise against the house of Jeroboam with the sword” (Amos 7:7-9).

Before considering the ways in which the plumb line is a foreshadowing of Christ, there is some potential ambiguity in the text that should be addressed. Many scholars argue that the translation “plumb line” is likely somewhat inaccurate. Instead, it is argued, the word should be lead or tin. On the one hand, is an interpretation that sees God standing on the wall of Jerusalem, which is thought to bring safety, and he tears off a portion of the wall, dropping it to the ground as a sign to the people that they have put their trust in the wrong thing. As commentator Anthony Gelston notes, “The image would be that of [God] standing on a tin wall, tearing off a piece, and throwing it into their midst. The implication is that the metallic wall, which from a distance seems strong, is actually weak. All their pretense is vain; their defense will come down.”1 Other commentators note that if the word is lead, then it may well refer to a plummet and line (plumb line)—and has usually been taken as an image of testing. Here, there’s a key observation, that “plummet and line were also used in the demolition that preceded repairs.”2 While the commentator notes that this means it could be a symbol of destruction rather than testing, I find it interesting that it is also points to the demolition that precedes repairs.

Consider the purpose of a plumb line—it provides an external reference to tell you whether the walls of a building are square, or whether they are leaning to one side or another. Attaching the line to anything on the wall would defeat the purpose: it must be a reference that is independent of that which is measures. And this is, I believe, the way that Christians must faithfully live, and preachers must faithfully preach, in any time, but particularly in fraught and ideologically tumultuous times. We have to redouble our efforts to look toward Jesus, and to judge our actions and our commitments first and foremost by him.

Christ is the plumb line. In Jesus, God became human in order to show humans what true humanity entails. When we veer to the one side, or the other, and away from Jesus, and the way he taught us to be and to live, we necessarily veer away from the plumb line. I am not the only one to make this association. Early Christian scriptural interpreter, Origen, and the great hymn writer Ephrem the Syrian, both make the connection between Jesus and the hardness of lead (adamant Origen calls it). Both articulate the ways in which the forces of wickedness will break themselves upon the firmness of Jesus. Ephrem makes the connection with the plumb line itself explicit, while connecting it also to the imagery of Jesus as the cornerstone:

Jesus would lead his detractors to the point of judging themselves, saying, “What do the vinedressers deserve?” [Mt 21:40]. They decided concerning themselves, saying, “Let him destroy the evil ones with evil” [Mt 21:41]. Then he explained this, saying, “Have you not read that ‘the stone which the builders rejected has become the head of the corner?’” [Ps 118:22 (117:22 LXX); 1 Pet 2:7.]. What stone? That which is known to be lead. For see, he has said, “I am setting a plumb line in the midst of the sons of Israel.” To show that he himself was this stone, he said concerning it, “Whoever knocks against that stone will be broken to pieces, but it will crush and destroy whomever it falls upon” [Lk 20:18]. The leaders of the people were gathered together against him and wanted his downfall because his teaching did not please them. But he said, “It will crush and destroy whomever it falls upon,” because he had resisted idolatry, among other things. For “the stone that struck the image has become a great mountain, and the entire earth has been filled with it” [Dan 2:35].3

In Amos, the plumb line is set in the midst of the people—a visible marker of judgment. On Holy Saturday, Christ becomes that plumb line set in the very midst of death. Where the prophet saw ruin ahead, the Church sees redemption begun, because the one who judges also forgives, and the one who created, restores and rebuilds.

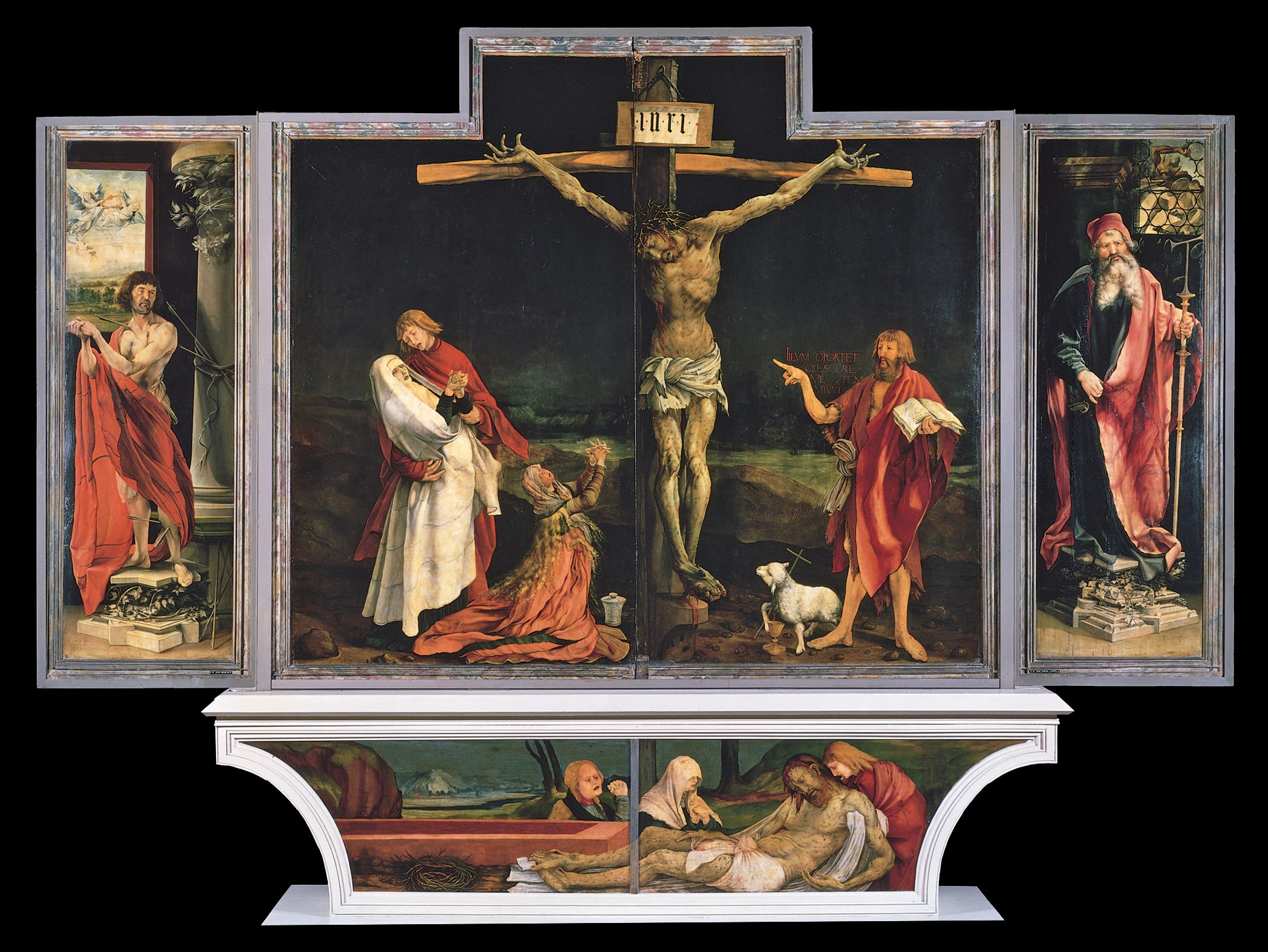

Yesterday was Good Friday, and those who attended services in the Episcopal Church likely participated in the veneration of the Cross. If so, you may have heard the following anthem from the Book of Common Prayer:

We glory in your cross, O Lord,

and praise and glorify your holy resurrection;

for by virtue of your cross

joy has come to the whole world.4

The Christian faith turns on reversal, but every reversal hinges upon one primary act—the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, which takes place in the context of Christ’s solidarity with humanity. We know the promise that the powerful and the powerless change places, the last become first and the first become last. This can happen because God provides the space and the template for this type of reversal and setting right through the incarnation, life, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Now we come to Holy Saturday, a day often overlooked in Christian imagination, yet one of profound theological weight. In the silence of this day, when no Eucharist is celebrated and the tomb remains sealed, Hans Urs von Balthasar invites us to contemplate the utter self-abandonment of the Son of God. In Mysterium Paschale, he writes that Christ’s descent into the dead is not merely a moment between crucifixion and resurrection, but the culmination of his obedience—a plunge into the dereliction of sin and death. By descending to the furthest edge of abandonment, to judge and transfigure it, Christ demonstrates his total identification and solidarity with us as finite human beings, “In that same way that, upon earth, he was in solidarity with the living, so, in the tomb, he is in solidarity with the dead.”5 On this day, he is the plumb line dropped to the depths of hell itself, revealing there is no place beyond the reach of redemption.

Rowan Williams in his book Resurrection: Interpreting the Easter Gospel notes how the “The exaltation of the condemned Jesus is presented by the disciples not as threat but as promise and hope. The condemning court, the murderous ‘city’, is indeed judged as resisting the saving will of God; but that does not mean that the will of God ceases to be saving.”6 This is why we can call the Friday when we commemorate the death of Jesus, “Good” and why we can say or sing an anthem in which way claim that “…by virtue of your cross joy has come to the whole world.” The plumb line of Jesus has been held up to the structures of this world and has found them lacking and harmful, but while there is judgment there, it is judgment that leads to redemption, destruction that will lead to renewal.

To my fellow preachers, I say, be ready to follow where scripture and your contemplation of Jesus’ ministry and teaching take you in regard to the messages you deliver. As always, consider your particular congregation: you will know their strengths, their weaknesses, the things at which they excel and the things that they find challenging in the Christian life. Demonstrate your care for them in the midst of your shared work and life, and trust that you will find the words to offer appropriate challenges to them so that they might see the dangers inherent in actions and practices they might otherwise accept without question. If we who proclaim the gospel are to be accused of partisanship, let it be as partisans for Christ who are unafraid to challenge the actions of anyone or any party who happens to be in power when their behavior runs counter to the gospel we proclaim and the Lord we serve. We must be willing to speak directly to issues of right and wrong without playing favorites or accepting excuses.

This is not a new idea. American Baptist and proponent of the Social Gospel Samuel Zane Batten argued in 1903 that “in every Christian Church there ought to be an atmosphere so intense, a sentiment so strong, a passion for righteousness so deep, that the political corruptionist and commercial sharper [i.e. swindler] should be compelled to reform or surrender [their] membership.”7 In the 1960’s Jesuit Gustave Wiegel wrote in the Atlantic that “The idea of salvation includes a way of life on earth, here and now. A way of life produces a visible comportment affecting others, and that must be a concern of the directors of the visible order of the commonwealth.”8 Speaking even more broadly, theologian and Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple, in his book The Hope of a New World states that “To worship is to quicken the conscience by the holiness of God, to feed the mind with the truth of God, to purge the imagination by the beauty of God, to open the heart to the love of God, to devote the will to the purpose of God.”9

It is, in other words, impossible to either worship or preach truthfully and faithfully without coming into conflict with many of the accepted ways of the world. This is a situation that could easily lead us to become judgmental and to replace the way of Jesus with our own way, to counter one person’s idolatry with our own. The only means to combat it is a combination of humility, faithfulness, and community—constantly looking toward Jesus not only on our own, but in solidarity with other Christians. Seeing things distinctively as individuals, and sharing them together as a community, while each centering ourselves on Christ, is one way to avoid going to extremes based on our own inclinations.

On this day, when Jesus’ body lay in the tomb while he proclaimed the message of salvation even to the spirits in prison, i.e. the dead (cf. 1 Peter 4:6 and look up “Harrowing of Hell”), we can be hopeful about the meaning of Christ with us, Christ as the plumb line, the moral measure of God’s people, the cornerstone of the Kingdom, the Judge—and also the strength and hope who empowers us to interrogate our own bias, tear down our own idols, and then speak truthfully to the world around us, saying what must be said in the name of Jesus.

As we sit in the quiet of Holy Saturday, may we allow the plumb line of Christ to drop in the midst of our lives—revealing what leans, what crumbles, and what, by God’s grace, might yet be renewed or rebuilt.

Anthony Gelston, “Amos,” in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, James D.G. Dunn, John W. Rogerson, eds., 694

Michael L. Barré, “Amos,” in The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, Raymond E. Brown, Joseph Fitzmyer, and Roland E. Murphy, eds., 214

Alberto Ferreiro and Thomas C. Oden, eds. The Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, Volume 14: The Twelve Prophets. Westmont: InterVarsity Press, 2003., 238

The Book of Common Prayer 1979, 281

Hans Urs Von Balthasar, Mysterium Paschale: The Mystery of Easter, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990. 161-162

Rowan Williams, Resurrection: Interpreting the Easter Gospel (Clevland: The Prilgrim Press, 2002), 3.; “The court and city that condemned Jesus is still engaged in judging and condemning him as it confronts his church. And insofar as it continues to judge and condemn, it continues to invite the judgment of its victim, whom God has approved and exalted. So, at the simplest level, we have to do with a straightforward reversal of roles: the condemned and the court change places, the victim becomes the judge. And this as it stands would have been a readily intelligible theological move. The idea that those who are now poor and despised will at the last day be endowed with the authority to judge those who judged them is familiar enough from Jewish apocalyptic literature, from Daniel to Qumran and later. But the gospel of the resurrection goes on to a more profound and startling reversal. The exaltation of the condemned Jesus is presented by the disciples not as threat but as promise and hope. The condemning court, the murderous ‘city’, is indeed judged as resisting the saving will of God; but that does not mean that the will of God ceases to be saving. The rulers and the people are in rebellion; yet they act ‘in ignorance’ (Acts 3:17; cf. Luke 23:34), and God still waits to be graciously present in ‘times of refreshing’ (Acts 3:19). And grace is released when the judges turn to their victim and recognize him as their hope and their savior.”

Samuel Zane Batten, “The Church as Conscience Maker,” The Watchman (1894-1906); Jan 8, 1903; 85, 2; ProQuest pg. 11

Gustave Weigel, The Church and the Public Conscience, The Atlantic August 1962 Issue

William Temple, The Hope of a New World, New York: MacMillan, 1942., 30